It may seem like stating the obvious, but children should be children.

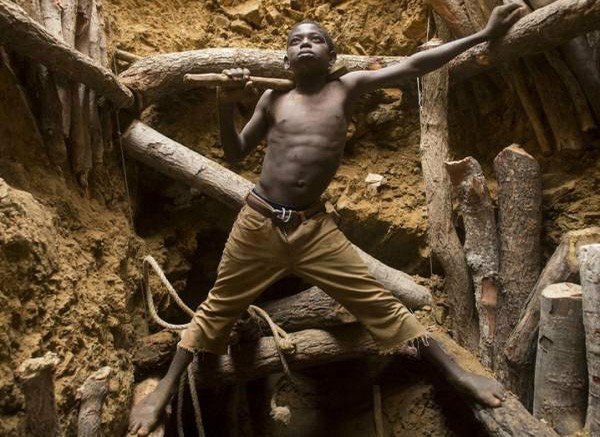

Unfortunately, child labor is a sad but widespread reality. It has always been found particularly in disadvantaged contexts in which they are forced to work so they and their families can survive. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), around 152 million children between the ages of 5 and 17 are victims of child labor in the world. Most work in farming, followed by the services and industrial sectors, particularly in mines. Figures which, as the ILO itself and UNICEF warn, could increase due to the poverty related to the COVID-19 crisis.

By definition child labor is any kind of activities which is mentally, physically, socially or ethically dangerous for children. The worst cases of child labor include those that put the child's health, safety or morality at risk.

Still, with the onset of new technology child labor is gradually changing its face.

Children should be entitled to access quality education and develop through the power of play anywhere in the world.

But you cannot call it play if you can make money out of that! Children are among the biggest stars of the web, earning millions through influencer deals with blue-chip brands or game platforms and social network’s partner programs, which gives creators a cut of ad revenues. Indeed, they have a major influence on other children who try to emulate them in every possible way. The “Kidinfluencers” phenomenon is taking over mostly in developed countries.

But, is kidfluencing work?

Some parents of influencers point out that the kids are just having fun or are barely conscious of what they are doing (brilliant and terrifying at the same time Julia Carrie Wong for The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/media/2019/apr/24/its-not-play-if-youre-making-money-how-instagram-and-youtube-disrupted-child-labor-laws ).

The boundary between innocent childish leisure and work imposed by parents is very thin especially when considering that every dollar a kid earns belong to his parents since they don’t even own their social media accounts. Many platforms ban children under thirteen from having accounts, which means that no pre-teen stars own the accounts to which the platform pays a share of advertising revenue. Influencer arrangements – in which brands pay influencers to post a photo or video of themselves promoting a product – take place off platform, and are presumably negotiated by parents.

So, in a provocative comparison, can be claimed that online platforms are the modern mines?

So much is said about “Kidinfluencers” phenomenon not only to safeguard children’s privacy but also to protect them from exploitation with special laws.

Indeed, for these children all of this is more than just fun and games. It is a multimillion-dollar market which badly hides huge economic interests.

“Kidinfluencers”, although celebrities, remain above all minors to protect, the same protection that their 'follower' peers, bewitched by this incredible success, deserve. Indeed, the isolation imposed by the current pandemic situation has made web addiction much worse.

negg® Group is strongly opposed to the exploitation of child labor in all forms even if on online platforms. For this very reason it is crucial that online platforms deliver more information on current legislation.

Fight against the commercial exploitation of the image of minors and avoiding contents that are detrimental to their dignity as well as physical and psychological integrity is a duty that all IT operators should give priority, always and however.